What Happened to the Ozone Layer?

3 Environmental Problems We Actually Fixed

By

Lynn Celek

on

April 10, 2025

Growing up in the ’80s and ’90s, recycling, conserving water and energy, and the ozone layer were common topics.

Today, we still talk about recycling—mostly about how we’ve failed at it. We still hear about conserving water and using LED lights to save energy.

But the ozone layer? Not a word. I forgot it exists.

With Earth Day right around the corner, I figured it was time to check in on the infamous hole that haunted my childhood. While I was at it, I also followed up on two other environmental fears from that era: acid rain and endangered bald eagles.

1. The Ozone Layer: What Happened to the Hole Over Antarctica?

What is the ozone layer (and what was “the hole”)?

Why are rising UV levels dangerous?

Without enough ozone, more UV-B radiation reaches the Earth’s surface. This increases skin cancer and cataract rates in humans and can weaken immune systems. But it also affects the environment: UV rays can damage phytoplankton, the base of ocean food chains. It can also harm young plants, especially crops. Some amphibians and fish are also vulnerable to increased UV, especially in their early life stages.

What did we do about it?

The ozone hole peaked in 2000—not 1987

Despite the 1987 Montreal Protocol, the ozone hole didn’t hit its largest size until 2000. It ballooned to cover an area about the size of North America (28.4 million square kilometers).

Why? Two main reasons:

There was a gradual phase-out of CFCs. Some products using CFCs were still being sold in the 1990s.

CFCs are extremely long-lasting—they can stay in the atmosphere for 50 to 100 years. It took time for emissions to stop and even longer for the existing chemicals to break down.

How big is it now, and when will it be fully healed?

By 2024, the average size of the hole had shrunk to about 20 million square kilometers, and scientists say it’s on track to keep getting smaller.

The timeline for healing:

By 2040, the ozone layer should return to 1980 levels over most of the globe.

By 2066, the Antarctic hole—the worst-affected area—should be fully healed.

Why was it worse over Antarctica?

It comes down to the cold.

Antarctica’s stratosphere gets so cold that special high-altitude clouds form. These clouds help turn chlorine from CFCs into a more reactive form. When sunlight returns in the spring, that reactive chlorine kicks off chemical reactions that destroy ozone.

Strong polar winds (the polar vortex) also trap these chemicals in place, making the damage worse.

You can learn more here if you want the deeper science.

2. Acid Rain: What It Is and How We (Mostly) Solved It

What is acid rain?

Why was it such a big deal in the '80s and '90s?

What did we do about it?

How much progress have we made?

According to the EPA, sulfur dioxide emissions have dropped by more than 90% since the 1980s. Nitrogen oxide levels are also way down. As a result, acid rain has mostly disappeared across the U.S. and much of Europe. Forests and lakes are slowly recovering.

Is acid rain still a problem anywhere?

Yes—acid rain hasn’t gone away everywhere. It’s still a serious issue in parts of Asia and Africa. There, it continues to damage forests, farmland, and water systems.

But the higher pollution in those areas doesn't affect the U.S. like CFCs did. Why?

Why it doesn't drift over to us like CFCs did

The pollutants that cause acid rain (sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides) don’t last long in the air. They usually fall to Earth as acid rain within a few days, so the pollution tends to stay regional.

By contrast, CFCs (the chemicals that damaged the ozone layer) are extremely stable and float high into the stratosphere, where they can circulate around the globe for decades.

So while air does move, only some kinds of pollution travel long distances, and acid rain isn’t one of them.

3. Bald Eagles: How They Went from Endangered to a Conservation Success

Why were bald eagles in trouble?

By the 1960s, the U.S. national bird was nearly gone from the lower 48 states. The culprit? A pesticide called DDT. It didn’t kill bald eagles directly, but it weakened their eggshells, making them too fragile to survive incubation.

At their lowest point, there were just 417 nesting pairs left in the continental U.S.

What did we do about it?

In 1972, the U.S. banned DDT. It was a turning point—but recovery wasn’t immediate.

Throughout the 1980s, bald eagle populations were still struggling. DDT lingered in the environment, and the eagles’ slow reproductive cycle made progress slow. Habitat loss and illegal hunting didn’t help either.

In 1978, bald eagles were officially listed as endangered in most of the country under the Endangered Species Act.

When did things turn around?

By the 1990s, thanks to continued protections, cleaner waterways, and habitat restoration, bald eagle numbers started to climb.

By 2007, they had recovered so successfully that they were removed from the endangered species list entirely.

As of 2024, there are over 316,700 bald eagles in the U.S.—including more than 71,400 nesting pairs.

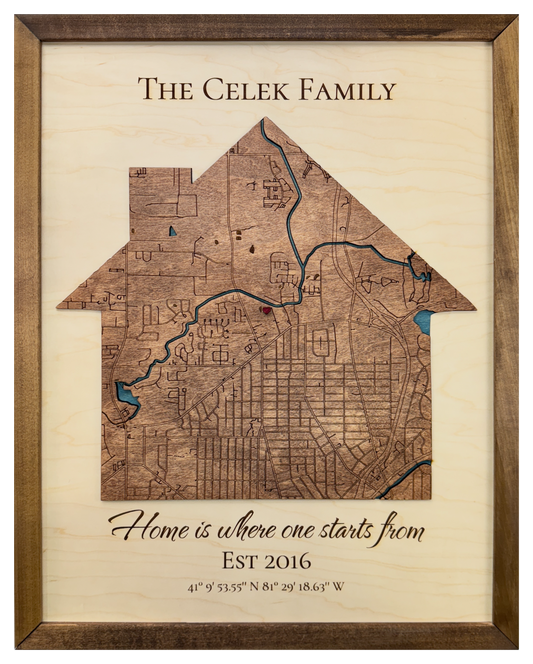

At MapCuts, We're Doing Our Part, Too

While these environmental wins came from sweeping policy changes, many fixes come from small, steady efforts.

At MapCuts, we make wooden maps. That means we use trees. It also means we think carefully about how to give back.

That’s why, for every map sold, we help plant one tree through our partnership with One Tree Planted. They're a nonprofit that supports reforestation projects around the world, including in the southeastern U.S., where we source much of our wood.

We also make all our maps in Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio—no overseas production, no long-distance shipping.

So while we’re not saving the ozone layer, we’re still planting seeds—literally—for a healthier planet.

If you’re looking for a gift with a little more meaning, shop our collection and help plant a tree with your map.

Blog References

European Environment Agency. (n.d.). What is the current state of the ozone layer?https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/topics/in-depth/climate-change-mitigation-reducing-emissions/current-state-of-the-ozone-layer

GovInfo. (2025, February 6). The bald eagle: An endangered species success story. https://www.govinfo.gov/features/bald-eagle-success-story#:~:text=In%20the%201960s%2C%20the%20National,leading%20to%20the%20bird's%20extinction.

NASA Earth Observatory. (2024, September 28). Ozone hole continues healing in 2024. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/153523/ozone-hole-continues-healing-in-2024

NASA Earth Observatory. (n.d.). Sulfur dioxide emissions fall in China, rise in India. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/91270/sulfur-dioxide-emissions-fall-in-china-rise-in-india#:~:text=A%20new%20study%20by%20researchers,modelers%20have%20taken%20into%20account.%E2%80%9D

The Borgen Project. (n.d.). 10 facts about pollution in Africa. https://borgenproject.org/pollution-in-africa/

UN Environment Programme. (n.d.). About Montreal Protocol. https://www.unep.org/ozonaction/who-we-are/about-montreal-protocol

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Air quality national summary. https://www.epa.gov/air-trends/air-quality-national-summary

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (n.d.). Eagle population status. https://www.fws.gov/project/eagle-population-status